30 Years Later, An Appreciation of the Desmond Howard Fade/Slant Offense

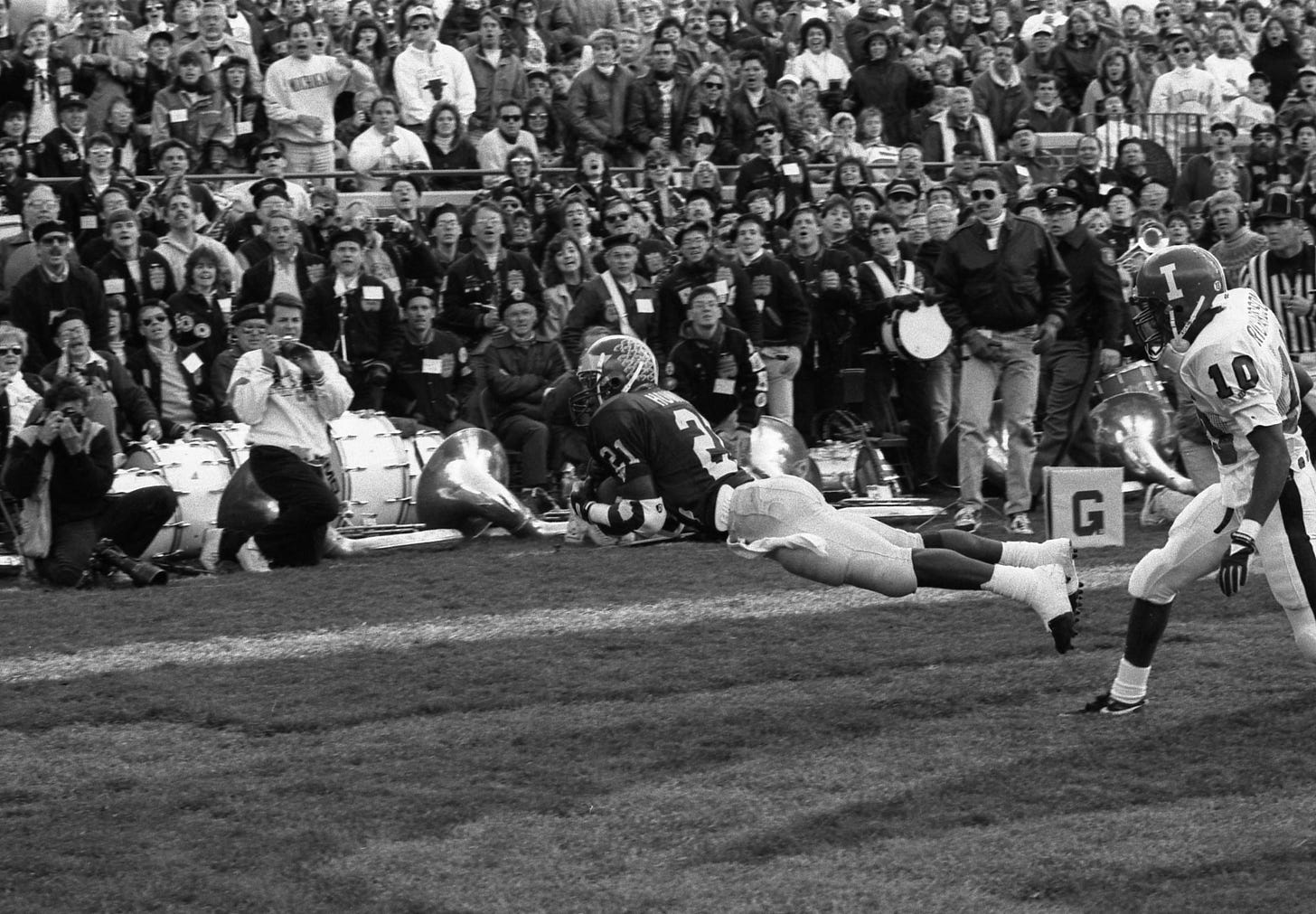

A punt return sealed the 1991 Heisman Trophy. Dominating the goal line as a 5-foot-9 wide receiver put Desmond Howard in position to strike the pose.

“Which position is hardest to play in team sports?” is an endless debate that’s far too subjective to answer.

Cornerback is high on the list, at least. When’s the last time you tried running backwards as fast as you can? It’s not easy to do without tripping. Now imagine having to mirror a very good athlete while doing so—and you don’t know where they’re going.

Corners in 1991 usually played on an island. This was the era of run-first offense; nearly as many teams ran for 2,000 yards (43) as threw for 2,000 (56).1 You were more likely to see one wide receiver on the field than four. The I-formation ruled the day. Throwing more than necessary was a needless risk—for most teams, at least.

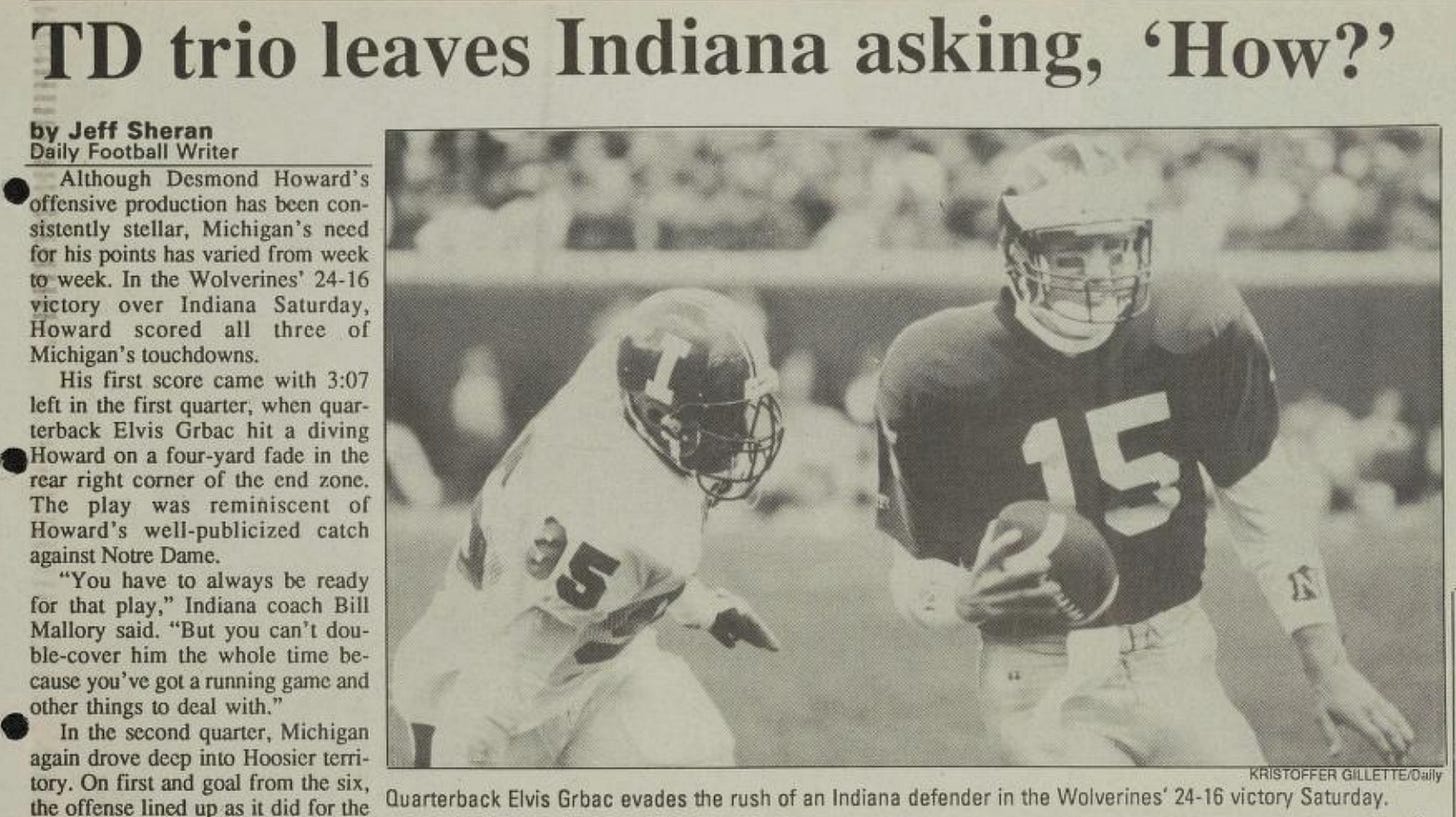

When Michigan reached the red zone in 1991, Desmond Howard put cornerbacks in an impossible bind. Cheat to the inside and he’d make a spectacular catch on a fade route. (See above.) Position on the outside to stop the fade, however, and he’d run a slant so quick it often defeated safety help. Put a hard double on him and the Wolverines could run into a light box with a running back trio that combined for 25 touchdowns; Tyrone Wheatley was the third-stringer.2

Howard announced his Heisman candidacy with three touchdown receptions, all from inside 20 yards, in the opening win over Boston College. (He also returned a kickoff for a touchdown.) The first came on a fade. The second, a slant.

The third was a post route, which I wanted to categorize as a late-breaking slant, the spiritually accurate description of the route’s function in this case. I resisted that urge in going back through all 23(!) of Howard’s touchdowns in 1991, 19 of which came through the air. Here are the routes that Howard scored on:

Fade - Five

Slant - Five

Post - Four

Screen - Two

Out, Fly, Corner - One apiece3

In three different games—Boston College, Michigan State, and Indiana—Howard hit paydirt on both a fade and a slant. Seven scores in a row, touchdowns #10-16, all occurred on one of those two routes.

Even in an era that features smaller receivers more than ever, watching the 5-foot-9 Howard dominate the red zone is an astonishing experience. The iconic touchdown against Notre Dame isn’t even his most impressive catch once you remove the context. This is impossible body control:

The goal-line fade is rightly maligned in modern football as a low-percentage play. While I don’t have these numbers on hand, I feel safe in assuming the Desmond Howard fade had a significantly higher expected value than the average lob to the back pylon.

Howard needed little space to create separation. His quick feet at the line made it very difficult for defenders to tell which direction he’d release into his route. His centerfielder-like ball tracking allowed Elvis Grbac to throw the ball towards a general area.

The fade/slant threat presented like that of a dominant two-pitch reliever in baseball, using the same initial delivery to produce two divergent results. Cheat on the fade/fastball and the slider/slant would look comically easy.

As Bob Griese says in that clip, this is checkers, not chess. Football doesn’t need to be complicated when great athletes are utilized based on their strengths. Gary Moeller didn’t need to do anything more complicated than install a couple option routes4 in a power running scheme to produce one of the nation’s most explosive offenses.

Is there a lesson in here about the program under Jim Harbaugh? Yes! But I’d rather continue discussing Howard.

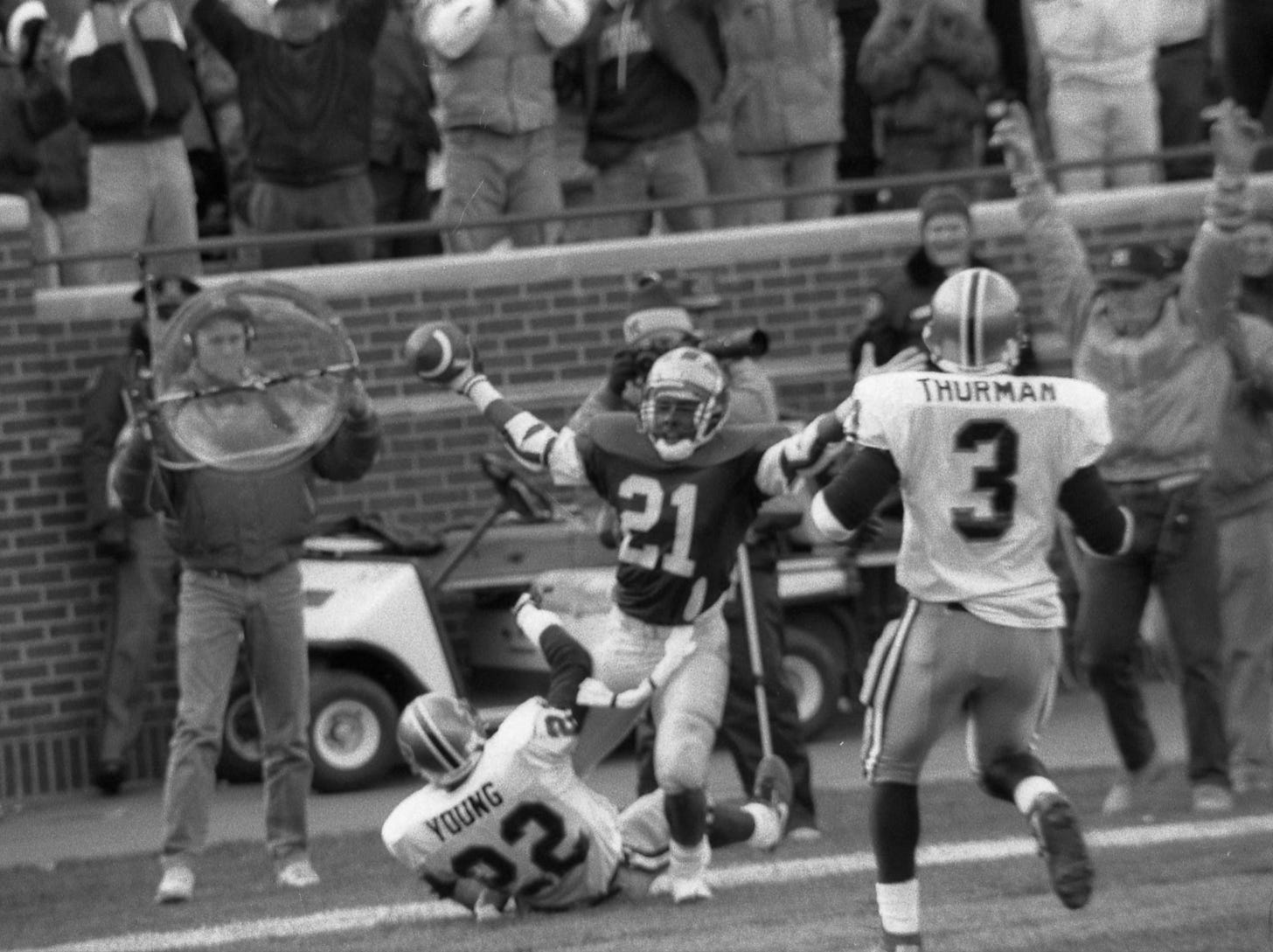

Here is Howard’s third touchdown catch from that Indiana game. The Hoosiers weren’t oblivious under Bill Mallory—they attempted to slide a second defender under the slant. The problem is Grbac knew his receiver’s capabilities. He fired it early, high, and a shade behind:

From the Michigan Daily:

Mallory was asked why he didn’t put two defenders on Howard after the junior split end had already burned Richardson once.

“He was double-teamed,” Mallory said. “The inside guy was supposed to come over if he cut in, but he didn’t react fast enough.”

You can feel Mallory’s resignation. Someone broke the system.

Howard tied for the national lead in both touchdowns (23) and points (138) with San Diego State running back Marshall Faulk, the NFL Hall of Fame inductee who played significantly easier competition. Next came Stanford’s 238-pound running back Tommy Vardell (22 TDs, 132 points) and Notre Dame’s Jerome “literally nicknamed The Bus” Bettis (20 TDs, 120 points).5

Faulk touched the ball 220 times in 1991, Vardell 273, and Bettis 185. Howard totaled 110 and needed 35 combined kickoff and punt returns to accumulate even that many. He scored a touchdown every 3.6 times he touched the ball on offense.

The next receiver on the list, Pacific’s Aaron Turner (18 TDs, 108 points), played two games against FCS (then I-AA) competition—and two more against programs that’d drop football within the next year (Cal State Fullerton and Long Beach State, the latter of which had Terrell Davis and still went 2-9 in ‘91).

The NCAA’s official team stats were tallied before the bowl games—they haven’t updated these years for reasons I cannot comprehend—and scanned from a printout made on my fourth birthday. Michigan finished tied for fourth in the country in scoring offense. Howard’s 23 TDs accounted for 42.6% of the team’s total; they’re also more than 22 entire-ass offenses scored that season.6

While Howard accumulated far bigger numbers in other games, his stat line against Indiana may be my favorite: five catches for 32 yards (long of 12) and three touchdowns. A 5-32-3 line looks like it should be in the rushing section.

“Magic” played one of the greatest seasons by a receiver in the history of college football only in part because he could score from anywhere on the field. He also accomplished it by becoming one of the nation’s most effective goal-line finishers in any weight class at 176 pounds.

When Howard stuck his foot in the ground, he chose one of two directions, and made himself a giant.

In 2019, 78 teams rushed for at least 2,000 yards and 116 threw for at least 2,000. Most teams now play 2-3 more games than they did in 1991.

Wheatley was also the other guy on kickoff returns with Howard. Diabolical.

Howard’s non-receiving touchdown breakdown: two rushing (both true reverses, not end-arounds), one kickoff return (BC), one punt return (Hello, Heisman).

Howard’s first read on The Catch was a quick hitch, as you can hear in the video embedded in the post. Notre Dame overplayed the hitch. That proved a mistake.

All individual stats via sports-reference.

Minnesota finished dead last with 12 TDs in 11 games. Head coach John Guntekust, who’d taken over for Lou Holtz in 1985, was subsequently fired. It wound up being his only head coaching job in a career that spanned from 1967 to 2017.